Art takes us out of ourselves into the imagination of the artist – and can also open our own imaginations. For Lent this year, you are invited to look at a different piece of art each week, coupled with a scriptural reference, to explore and reflect upon different aspects of our Lenten journey, as we progress from wilderness to the Last Supper.

It may be helpful by way of preparation to look at the image, read the description, and reflect upon the passage of scripture each week.

Each session will last an hour and will be presented in the church and simultaneously via Zoom. Please click on the appropriate highlighted link each week for the next Zoom session, or for a recording of the previous session(s). If asked for a Zoom password, please use 07720.

Wednesdays at 12:30 CET, in the church or via Zoom.

- Week 1, 24 February: Reaping the Whirlwind – recording (Hosea 8.7)

- Week 2, 3 March: The Return of the Prodigal Son – recording (Luke 15.11-32)

- Week 3, 10 March: Ezekiel in the Valley of Dry Bones (Ezekiel 37.1-14)

- Week 4, 17 March: Last Scapegoat—A Requiem (Man of Sorrows/Suffering, Isaiah 53.1-9)

No recording available for week 4. - Week 5, 24 March: The Last Supper (Mark 14.12-26)

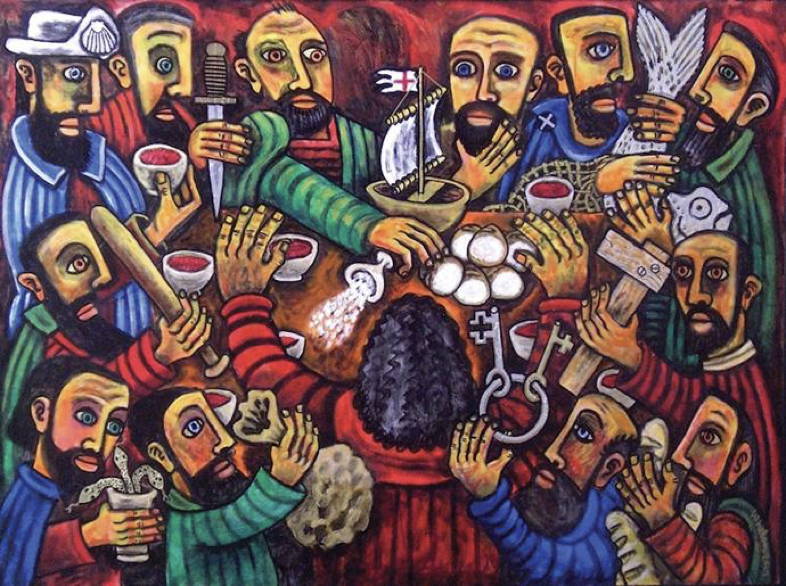

Week 5 – The Last Supper, by Brian Whelan

How to depict the 12 disciples has long been a perplexing problem for illustrators of the Last Supper. Artistic convention established that Peter should be presented as a curly-haired senior. John was often a beardless youth, leaning against Christ. Judas might be seated at the wrong side of the table, carrying his pouch with thirty pieces of blood money. But the remaining nine have come down to us in centuries of sacred art as a lineup of look-alikes. Brian Whelan, a London-born Irish artist, now living in the United States, has found a whimsical solution for the who’s who dilemma, inspired by his love of Celtic and English medieval art, where the sacred need not always be solemn or the holy without humour. In this view over Christ’s shoulders at the motley gathering in the Upper Room, Whelan has marked each disciple with emblems associated with their life, martyrdom, and patronage of groups and guilds. Peter, for example, displays the keys of the kingdom. Thomas holds a T-square as the favoured saint of architects. Bartholomew flashes a flaying knife as patron of butchers and tanners. A money bag is grasped by Matthew, the tax collector—not Judas, as you might expect. The betrayer of Christ has ominously spilled the saltcellar in imitation of Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece. These first followers of Christ might have been rough and not always ready, but seen here through the Saviour’s loving eyes they will be adequately equipped, each in their own way, to fulfil his Great Commission.

Mark 14.12-26

On the first day of unleavened bread, when the Passover lambs were sacrificed, Jesus’ disciples said to him, ‘Where would you like us to go and get things ready for you to eat the Passover?’

He sent off two of his disciples, with these instructions.

‘Go into the city, and you will be met by a man carrying a water-pot. Follow him. When he goes indoors, say to the master of the house, “The teacher says, where is the guest room for me, where I can eat the Passover with my disciples?” He will show you a large upstairs room, set out and ready. Make preparations for us there.’

The disciples went out, entered the city, and found it exactly as he had said. They prepared the Passover.

When it was evening, Jesus came with the Twelve. As they were reclining at table and eating, Jesus said, ‘I’m telling you the truth: one of you is going to betray me – one of you that’s eating with me.’

They began to be very upset, and they said to him, one after another, ‘It isn’t me, is it?’

‘It’s one of the Twelve,’ said Jesus, ‘one who has dipped his bread in the dish with me. Yes: the son of man is completing his journey, as scripture said he would; but it’s bad news for the man who betrays him! It would have been better for that man never to have been born.’

While they were eating, he took bread, blessed it, broke it, and gave it to them.

‘Take it,’ he said. ‘This is my body.’

Then he took the cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, and they all drank from it.

‘This is my blood of the covenant,’ he said, ‘which is poured out for many. I’m telling you the truth: I won’t ever drink from the fruit of the vine again, until that day – the day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.’

They sang a hymn, and went out to the Mount of Olives.

Week 4 – Last Scapegoat – A Requiem, by Alfonse Borysewicz

Catholic painter Alfonse Borysewicz often takes inspiration from scriptural passages and liturgical rites. He has created an impressive body of work that hangs not only in galleries and private collections but in churches, monasteries, and seminaries from Brooklyn to Grand Rapids, Michigan. In this work, the background is formed from shredded musical scores. The requiem, traditionally played at a funeral mass, here takes on physical form, as if rent and stained by ash like a mourner’s garments. In the right-hand corner, set within an outsize drop of blood, the Man of Sorrows bows his head and weeps. Whether it is for himself, the figure in front of him, or humanity in general is unclear. Yet for all these signs of grief, the mysterious figure in the foreground rises in regal purple, festooned with the roughly sketched feathers of an angel and a homespun halo. Grief still structures the composition—an unsettling cacophony playing in the background for all those with eyes to see and ears to hear—but it does not reign. If the amorphous white form on the left is a scapegoat, it has not faded away in ignominy but has risen again. The work’s ambivalent title becomes a prayer: perhaps this scapegoat truly is the last.

Isaiah 53.1-9 (Man of Sorrows/Suffering)

Who has believed what we have heard? And to whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed?

For he grew up before him like a young plant, and like a root out of dry ground;

he had no form or majesty that we should look at him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him.

He was despised and rejected by others; a man of suffering and acquainted with infirmity;

and as one from whom others hide their faces, he was despised, and we held him of no account.

Surely he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases;

yet we accounted him stricken, struck down by God, and afflicted.

But he was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the punishment that made us whole, and by his bruises we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray; we have all turned to our own way,

and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.

He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth;

like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent,

so he did not open his mouth.

By a perversion of justice he was taken away.

Who could have imagined his future?

For he was cut off from the land of the living, stricken for the transgression of my people.

They made his grave with the wicked and his tomb with the rich,

although he had done no violence, and there was no deceit in his mouth.

Week 3 – Ezekiel in the Valley of Dry Bones, by Cody F. Miller

Can these bones live? The answer to this question posed to the prophet Ezekiel seems painfully obvious in such a macabre setting, depicted in this mixed media collage by Cody F. Miller as a place of skull heaped on skull, where all hope is lost. In one of the great reversal narratives of the Bible, Ezekiel’s visionary vista of desolation and destruction undergoes an astonishing transfiguration. The jumbled bones knit together, take on flesh, and come to life as a sign of the future national revival of the Jewish people, held captive in Babylon, an image with universal meaning for other peoples in other valleys. Building up his composition from drawings and patterns made from magazine clippings, Miller depicts the moment of divine empowerment as coming with wind and fire like the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. In a pose that plays off the graveyard soliloquy scene in Hamlet, the prophet delivers God’s call to new life to just one of the many dead in this charnel heap, suggesting that collective renewal begins with transformed individuals. “My pieces are about hope,” says Miller. “Not necessarily in a bright way, but in a way that reveals the hidden fingerprint of God, letting us know, ‘I was here all along.’”

Ezekiel 37.1-14

The hand of the Lord came upon me, and he brought me out by the spirit of the Lord and set me down in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. He led me all round them; there were very many lying in the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, ‘Mortal, can these bones live?’ I answered, ‘O Lord God, you know.’ Then he said to me, ‘Prophesy to these bones, and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. Thus says the Lord God to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. I will lay sinews on you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the Lord.’

So I prophesied as I had been commanded; and as I prophesied, suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone. I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had come upon them, and skin had covered them; but there was no breath in them. Then he said to me, ‘Prophesy to the breath, prophesy, mortal, and say to the breath: Thus says the Lord God: Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live.’ I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude.

Then he said to me, ‘Mortal, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They say, “Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.” Therefore prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord God: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. And you shall know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people. I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken and will act, says the Lord.’

Week 2 – The Return of the Prodigal Son, by Marie Romero Cash

In our time of social distancing, this carved wood sculpture of the return of the prodigal son by Marie Romero Cash reminds us what it means to hold and to be held. A native of New Mexico, Cash works with natural pigments and local woods like pinyon pine to make her folk art pieces, keeping alive the traditions of the Hispanic “saint-makers” who once crafted simply styled holy images for outlying communities in what is now the American Southwest, at a time when religious artefacts from Mexico were in short supply. The father from the parable lifts his eyes toward heaven in gratitude for the return of his wayward son, now safely at rest in his arms. The father’s features and kneeling pose evoke imagery of Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane, praying for the will of God to be done. Says Cash, “It hurts not to be able to reach out and touch a loved one, especially if you live alone. You feel like an orphan with no one but yourself to navigate through days that run together. In this sculpture, the son is back in an embrace he has missed for so long.”

Luke 15.11-32

Jesus went on: ‘Once there was a man who had two sons. The younger son said to the father, “Father, give me my share in the property.” So he divided up his livelihood between them. Not many days later the younger son turned his share into cash, and set off for a country far away, where he spent his share in having a riotous good time.

‘When he had spent it all, a severe famine came on that country, and he found himself destitute. So he went and attached himself to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him into the fields to feed his pigs. He longed to satisfy his hunger with the pods that the pigs were eating, and nobody gave him anything.

‘He came to his senses. “Just think!” he said to himself. “There are all my father’s hired hands with plenty to eat – and here am I, starving to death! I shall get up and go to my father, and I’ll say to him: ‘Father; I have sinned against heaven and before you; I don’t deserve to be called your son any longer. Make me like one of your hired hands.’ ” And he got up and went to his father.

‘While he was still a long way off, his father saw him and his heart was stirred with love and pity. He ran to him, hugged him tight, and kissed him. “Father,” the son began, “I have sinned against heaven and before you; I don’t deserve to be called your son any longer.” But the father said to his servants, “Hurry! Bring the best clothes and put them on him! Put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet! And bring the calf that we’ve fattened up, kill it, and let’s eat and have a party! This son of mine was dead, and is alive again! He was lost, and now he’s found!” And they began to celebrate.’

‘The older son was out in the fields. When he came home, and got near to the house, he heard music and dancing. He called one of the servants and asked what was going on.

‘ “Your brother’s come home!” he said. “And your father has thrown a great party – he’s killed the fattened calf! – because he’s got him back safe and well!”

‘He flew into a rage, and wouldn’t go in.

‘Then his father came out and pleaded with him. “Look here!” he said to his father, “I’ve been slaving for you all these years! I’ve never disobeyed a single commandment of yours. And you never even gave me a young goat so I could have a party with my friends. But when this son of yours comes home, once he’s finished gobbling up your livelihood with his whores, you kill the fattened calf for him!”

‘ “My son,” he replied, “you’re always with me. Everything I have belongs to you. But we had to celebrate and be happy! This brother of yours was dead and is alive again! He was lost, and now he’s found!” ’

Week 1 – Reaping the Whirlwind, by David Baird

David Baird’s artistic practice is intimately entwined with his work as an architect. He begins each day by painting, experimenting with countless geometric variations. In a recent series, he overlays biblical texts with columnar forms which migrate across collaged pages. Even when he is not working directly with scripture, an exegetical impulse runs through much of Baird’s work, especially the wooden constructions he produced for his show at Wesley Theological Seminary, entitled Between the Lines: Biblical Speculations. One might expect an architect to render Noah’s ark or the tower of Babel as recognizable, even functional forms. Yet Baird’s interest lies in puzzling out the logic of the text itself, assessing how narratives are fashioned into complex, incongruous, even self-defeating structures. The work above represents a bold new direction for Baird, in which he has begun to scale up these constructions and place them in local Nevada landscapes, not unlike those of biblical lands. Here, his twisting forms feel like wind-worn rock formations, recalling Hosea’s warning that those who “sow the wind . . . shall reap the whirlwind” (8:7). Yet his sculpture also seems to keep watch from the margins, standing austere and inscrutable like a prophet.

Hosea 8.1-8

Set the trumpet to your lips!

One like a vulture is over the house of the Lord,

because they have broken my covenant,

and transgressed my law.

Israel cries to me,

‘My God, we—Israel—know you!’

Israel has spurned the good;

the enemy shall pursue him.

They made kings, but not through me;

they set up princes, but without my knowledge.

With their silver and gold they made idols

for their own destruction.

Your calf is rejected, O Samaria.

My anger burns against them.

How long will they be incapable of innocence?

For it is from Israel,

an artisan made it;

it is not God.

The calf of Samaria

shall be broken to pieces.

For they sow the wind,

and they shall reap the whirlwind.

The standing grain has no heads,

it shall yield no meal;

if it were to yield,

foreigners would devour it.

Comments are closed.